“Regime uncertainty” should be our bywords for understanding the economy of 2025. Trump’s push for “state capitalism,” ranging from tariffs to taking federal stakes in companies to industrial policy to jawboning companies to fire executives to targeted regulatory carveouts, has created a chaotic, pay-to-play environment in which firms find they can get favorable treatment by contributing to Trump’s political success, but the basic rules of the economic game are unpredictable and open to constant negotiation. That unpredictability has in turn deterred private investment and brought on stagflation.

Economist Robert Higgs developed the concept of regime uncertainty to explain why American recovery from the Great Depression was so slow. Investors feared for the security of their contracts and their private property rights as FDR turned explicitly anti-business during the 1936 presidential campaign. As a result, private investment stagnated and the economy tipped back into recession, prolonging the Great Depression. Investor confidence didn’t return until after the war, when it launched an economic boom.

Regime uncertainty was on my mind when I watched the fateful “Liberation Day” press conference in the Rose Garden on April 2, when President Trump held up the schedule of so-called “reciprocal tariffs” that would apply to imports from other countries. The tariff rates themselves were extremely high, but more than that, they were absurd and irrational. They had no logical basis in law or economics. I immediately moved my retirement savings out of US equities into global equities and bought physical gold with all my family’s free cash. After most of the tariffs were rolled back, I gradually started shifting back to a 60-40 US-global equities mix, which is still overweighted to international stocks compared to most Americans’ portfolios.

I didn’t shift to gold or global stocks because I thought the tariffs themselves would be so destructive, but because I lost all confidence in this administration’s economic policy team. I figured we were in for a wild ride, and unfortunately, we have been.

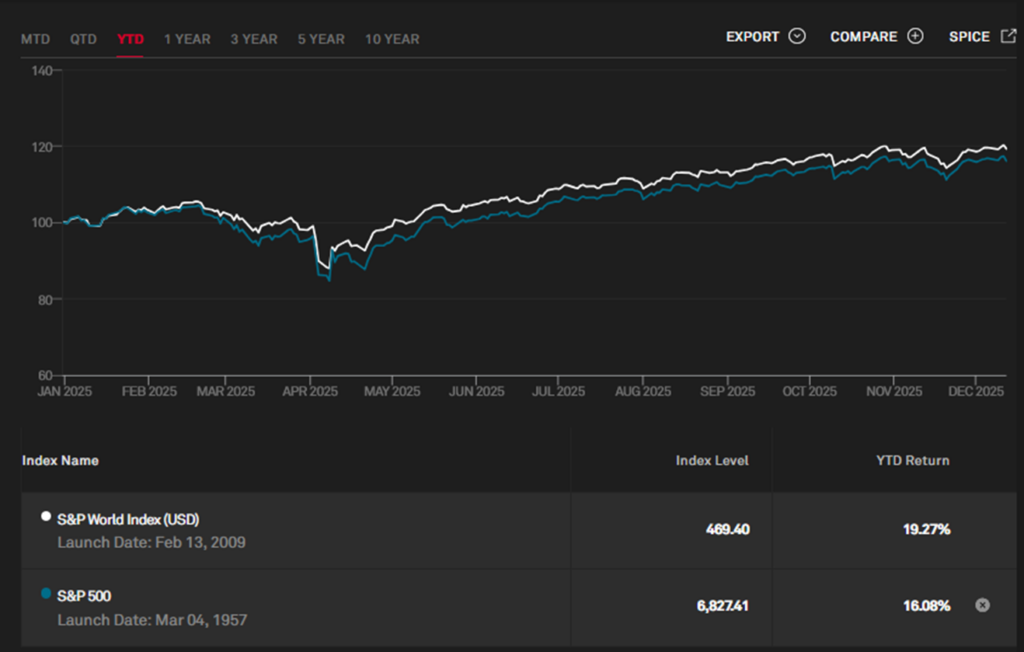

Regime uncertainty explains not just why global stocks have outperformed US stocks (Figure 1), but why gold has performed so well, despite reasonably moderate inflation (Figure 2). Gold is hedging not just ongoing inflation, but policy uncertainty more broadly.

Figure 1: S&P 500 Index vs. S&P Global Index, Jan. 2025 to Dec. 2025 (source: WSJ)

Figure 2: Gold Spot Price, Jan. 2025 to Dec. 2025 (source: TradingView)

Regime uncertainty explains another curious fact about the current US economy: the return of mild stagflation. With private investment lagging, unemployment has risen along with inflation. Macroeconomists would interpret this combination as an “adverse supply shock,” that is, a loss of productivity growth.

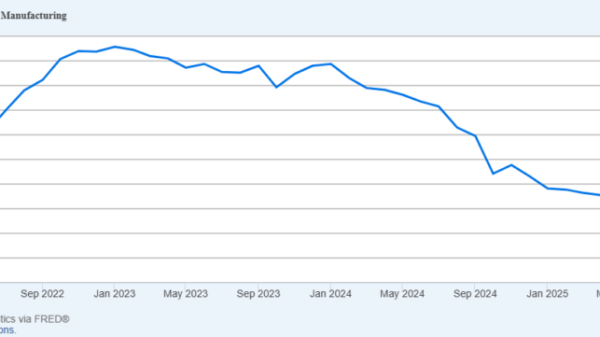

As Figure 3 shows, US job growth has slowed markedly since April. Monthly job growth since then has averaged a measly 35,000 workers, compared to over 100,000 every single month going back to October 2024.

Figure 3: US Nonfarm Jobs, Monthly Change, Jan. 2022 to Nov. 2025

The unemployment rate has also now risen a full percentage point since its 2023 low. Note that there is a gap in the series because of the government shutdown: the October figure is missing. The November figure is 4.6%, which means that the unemployment rate has risen a full half a percentage point just since June.

Figure 4: US Unemployment Rate, Jan. 2022 to Nov. 2025

Figure 5 shows monthly personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation rates up through November (excluding October). While this series is highly noisy, an upward trend since March is plainly apparent. Moreover, the disinflationary trend that we saw from the beginning of the series up until March has definitively come to an end. For the months through September, we had six straight months of PCE inflation near or above the Fed’s target. The last time that happened was the six months ending in June 2023.

Figure 5: US PCE Inflation, Monthly, Jan. 2022 to Sept. 2025

So far the data suggest the US economy is slowing, investors are hedging against something, and investors prefer to park their money abroad rather than in the US. But the smoking gun that suggests regime uncertainty is at fault is private investment. Real gross private investment is the series that Higgs himself uses to establish a “capital strike” during the late New Deal period.

What do we see when we look at US real gross domestic private investment in 2025? In Q2 2025, the quarter that includes Liberation Day, we see the largest single-quarter decline in US private investment since Q2 2020, the quarter most affected by the global pandemic (Figure 6). To see another decline as large, we have to go all the way back to 2009, during the throes of the Great Recession. Indeed, to find another quarterly decline as large outside the immediate period during or around an official recession, we have to go all the way back to Q1 1988. The just-released figures for Q3 show another decline in real private investment, of 0.3%.

Figure 6: US Real Gross Domestic Private Investment, Quarterly Growth, Q1 2020 to Q3 2025

All of this has been happening at the same time as an AI-fueled boom in capital investment for electricity generation and data centers has taken hold. Had this technologically driven boom not been ongoing, the effects of regime uncertainty on the US economy presumably would have been much worse.

Indeed, if we look at the components of private investment, “information processing equipment,” “software,” and “research and development” have contributed significantly to growth this year. But their growth has been more than offset in the last two quarters by declines in nonresidential structures and residential construction.

Why has regime uncertainty become such a problem? After all, the Trump Administration has made a verbal commitment to deregulation, and the tax cuts passed in the One Big Beautiful Bill should have incentivized business investment. But all of the deregulation enacted by the Trump Administration has come through executive orders and the rulemaking process, not legislation. A future administration could easily undo it. As a result, businesses lack the confidence that large capital investments will pay off in the long run.

The evidence suggests that to turn the American economy around, the Trump Administration needs to work through Congress to pass statutory deregulation, end its experiments with industrial policy, government ownership, and tariffs, and shift from a “deal-making” posture of transactional politics to a firm, credible commitment to enforcing a level playing field for private business. Without a believable shift in strategy, this administration risks incurring an economic malaise that could last for another three years.