On Sunday, October 26, Argentine President Javier Milei’s party, La Libertad Avanza, won big in the country’s legislative elections. In the lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, it won 50.4 percent of the available seats on a plurality — 40.7 percent — of the vote. In the upper house, the Senate, it won thirteen of 27 available seats for a net gain of six.

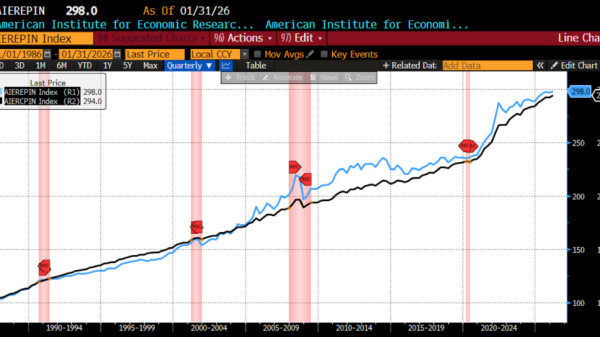

Many doubted such an outcome a month ago when, according to Polymarket, the party’s odds of winning most seats fell to a low of 52.5 percent, down from 89.5 percent on August 19. Argentina was, then, in the grip of one of its perennial economic crises, with the peso falling and bond yields rising. The fate of Milei’s bid to right the country’s economy by balancing the budget with deep spending cuts — which, as Noah Smith noted in July, had eliminated the budget deficit and brought inflation down from a monthly rate of 25 percent to 2.4 percent — hung in the balance.

The proximate cause of Argentina’s latest economic crisis occurred on September 7, when, with Milei’s sister embroiled in a corruption scandal, Alianza La Libertad Avanza suffered a heavy electoral defeat at the hands of the center-left Fuerza Patria. “Markets panicked,” The Economist reported, “worried that this signaled the end of popular support for his reforms, and the potential return of spendthrift Peronists. A sharp peso sell-off began, while investors ditched Argentine bonds.”

While Argentina is not alone in feeling the fiscal pain of rising bond yields, few countries nowadays worry very much about their exchange rates. But Argentina is different.

The Necessity and Peril of Foreign Currency Borrowing

The ultimate cause of Argentina’s crisis is its long history of fiscal and monetary mismanagement. It has defaulted on its international sovereign debt nine times, three of those in the past two decades, and suffered repeated bouts of high inflation. As a result, nobody will lend pesos to its government at a remotely affordable interest rate because they either might not get repaid at all (a hard default) or be repaid in currency which is worth much less than when they loaned it (a soft default).

So, to borrow the pesos it needs to finance its operations, the Argentine government first borrows dollars which it then exchanges for those pesos. But a government which borrows dollars must be able to repay dollars. So how does a government which borrows in a currency it doesn’t issue — which isn’t a “monetary sovereign” — get that currency? It has two sources.

Taxation is the first. The Argentine government could impose taxes on its population payable in dollars, but that merely transfers the problem of getting those dollars in the first place from the government to the taxpayers. To do so, those taxpayers would need to sell more to the United States (or anyone else who is willing to transact with them in dollars) than they buy from it. In short, Argentina would have to run a current-account surplus, something it has done only rarely in recent years.

Borrowing is the second. Here, however, the Argentine government is effectively buying dollars with pesos, and this is why the exchange rate — the peso price of dollars — matters. In April, 1,000 pesos bought you 93 cents; on September 21, it bought you just 68 cents. Milei’s government needed more pesos to buy the same amount of dollars, and this, as The Economist noted, raised the familiar specter of money printing and inflation, with the consequent flight from pesos and peso denominated debt, like Argentine government bonds, and the resulting fall in the currency and rise in bond yields.

The Folly of Fixed Exchange Rates

To protect themselves from such a situation, the Argentine government has tried to fix the exchange rate, but there are limits to this.

If the peso rises against the dollar, the Argentine central bank, as the issuer of pesos, can print them in unlimited quantity, using them to buy dollars, pushing the relative price of pesos down and the relative price of dollars up.

It is a very different situation when the peso is falling against the dollar. Then, the Argentine central bank must push the price of the dollar down relative to pesos by selling dollars for pesos, pushing the relative price of those pesos up. But the Argentine central bank only has access to a certain number of dollars so there are limits to how far it can pursue this policy. This is the great asymmetry at the heart of currency pegs like Argentina’s; as the British discovered in 1992, it is easy to weaken a relatively strong currency, but not to strengthen a relatively weak one.

In the run-up to the election, Argentina blew through its dollar reserves attempting to defend the peso’s peg. When it ran out of ammo, President Trump stepped in. However helpful, depending on the president is not a macroeconomic strategy for the long term.

The Prospects for Argentina

Milei aims to get Argentina’s borrowing under control so that it is less vulnerable to swings in the exchange rate. The country’s electorate gave him a vote of confidence this Sunday. Unlike voters in other countries, they might have felt a level of economic pain which has led them to acknowledge the need for Milei’s medicine.

With this mandate, work remains to be done. “The main problem is that Argentina has a large welfare state given the size and level of development of its economy, and a highly distorted tax and transfer system that funds it,” political economist Jean-Paul Faguet told Newsweek in September. “It only manages to remain stable during good times; a bad international economy or specific international shocks throw it out of kilter and into crisis.” Sunday’s election was a positive shock, with the peso and bond prices rising and yields falling on the news. But as long as Argentina’s structural problems persist, the economy – and the country – will remain vulnerable. Its welfare state must, like that in France, for example, be brought into proportion with the economy’s ability to support it and that will mean further cuts. With Milei up for reelection in 2027, much work remains for him to do.