President Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” (OBBB) is a mixed bag for the Federal Reserve. On the one hand, OBBB’s passage removes the near-term difficulty of conducting monetary policy in the face of huge swings in the Treasury General Account. On the other hand, it may make it more difficult for the Fed to see through its planned balance sheet reduction.

The Federal Reserve’s $7 trillion balancing act just got easier—and more complicated—thanks to President Trump’s historic $5 trillion debt ceiling increase. While this “One Big Beautiful Bill” resolved an unprecedented collision between fiscal brinksmanship and monetary policy, it created new challenges that could complicate Fed operations down the road.

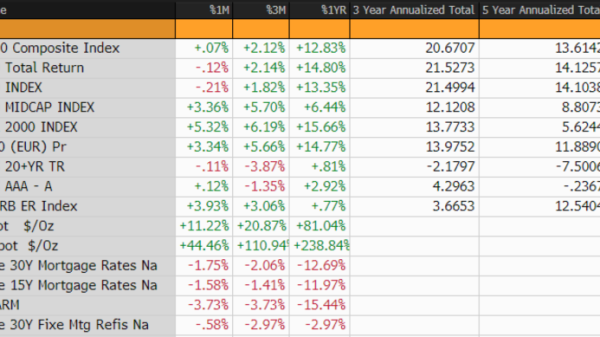

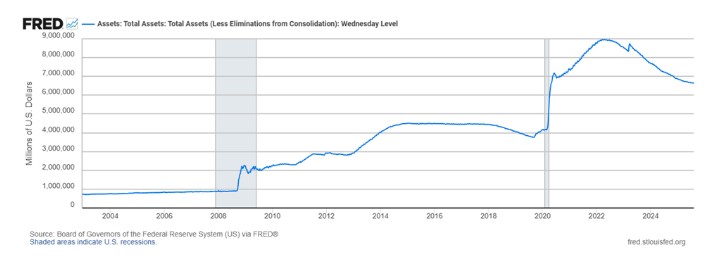

Let’s start with the Fed’s massive balance sheet. During the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed expanded its asset holdings from around $800 billion to nearly $9 trillion—that is, $9,000 billion. Then, in 2022, the Fed began slowly shrinking its balance sheet. It is not actively selling assets. Rather, it is not replacing a portion of its maturing bonds. The Fed intends to use this “balance sheet runoff” approach to transition from an abundant reserves to an ample reserves regime.

Plot data: here

The Fed’s balance sheet runoff approach was designed to run in the background, on autopilot, while interest rates did the heavy lifting of monetary policy. So far, it has reduced the balance sheet by approximately $1.7 trillion.

Before the passage of OBBB, debt ceiling politics created a roadblock for the Fed’s balance sheet runoff plans.

The Treasury has an account at the Fed known as the Treasury General Account (TGA), which is essentially the government’s checking account. Typically, the government will maintain a large balance in the TGA, in order to ensure it can make payments over the next few weeks. It will draw down this balance gradually, and replenish it as it sells bonds and receives tax payments throughout the year.

When the debt ceiling becomes binding, however, the TGA can increase reserve volatility. Unable to issue new debt, the Treasury must rapidly drain the TGA to keep the government funded. When the government spends this money, it flows into the banking system, causing bank reserves to spike. Then, when Congress raises the debt ceiling, the Treasury rebuilds its TGA balance by issuing new debt. That results in a sudden drain of reserves from the banking system. For example, after the debt ceiling was raised in June 2023, the TGA “increased by $600 billion over the short period of three to four months.”

Huge swings in the TGA balance create a dangerous scenario for the Fed. If bank reserves fall too quickly, financial markets might become volatile. This is especially difficult if the Fed is engaged in balance sheet runoff, since that also removes reserves from the system. Indeed, when the Fed faced this risk in March 2025, it slowed its balance sheet runoff. In other words, the Fed took its balance sheet runoff approach off autopilot to prevent a potential reserves shortage.

The OBBB raised the debt ceiling by $5 trillion—the largest increase in US history. This massive increase in the debt ceiling likely provides sufficient borrowing authority for the next five years, allowing the Treasury to operate normally without the dramatic swings in the TGA that complicated Fed policy. Correspondingly, the Fed can resume normal balance sheet runoff operations.

But solving one problem created another. The Congressional Budget Office projects that the OBBB will add $3.4 trillion to the national debt over the next decade—equivalent to roughly $340 billion in additional Treasury issuance each year. That creates a challenging market dynamic. Private markets must absorb both normal Treasury financing needs (approximately $3 trillion in maturing debt this year) plus the additional $340 billion annually. Assuming this increase in the supply of Treasuries outpaces demand, interest rates will be pushed up.

Presumably, the White House will not be happy about the prospect of paying higher interest rates on its debt. It may pressure the Fed to step back in as a buyer of national debt to help reduce the financial cost to the Treasury. Congress could even require the Fed to purchase more government debt, effectively ending the Fed-Treasury accord.

Even if the Fed is neither required nor pressured to buy more government debt, it will have to decide how to react to the corresponding interest rate movements. That, on its own, may push the Fed to reduce the pace of the balance sheet runoff or become a buyer once again.

Thomas Sowell famously quipped that there are no solutions, only tradeoffs. Fed officials can surely appreciate the sentiment. By raising the debt ceiling, OBBB takes them out of the reserve-volatility frying pan. It may also put them into the debt-monetization fire.