President Trump has, it is clear, upended the global trading system and America’s place in it through his aggressive use of tariffs as a tool of personal power. These actions would have shocked the Founding Fathers as offensive to the spirit of their new Constitution in a variety of ways. The fact that arguments in favor of their use are advanced by people who claim to be the most ardent supporters of the US Constitution might shock them even more. Yet perhaps their checks and balances might yet hold; we shall soon hear from the courts about that (the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments on July 31).

Let us begin, as is traditional, with a long list of abuses and usurpations that the President has perpetrated in the name of raising tariffs. We know that the President believes that “trade is bad” and “tariff is the most beautiful word in the dictionary” (the latter with some minor qualification). So, it should come as no surprise that he has been enthusiastic about raising tariffs.

In his first term, the President stuck to the old protectionist saw of using tariffs purportedly to address national security concerns under established powers used by many Presidents. This term, he discovered a new power, unappreciated by any previous President, in the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), passed in 1977 as a law which did not mention tariffs but allowed the President to “regulate imports” in the event of a national emergency. The President declared several emergencies, but the most important of those for our purposes was when he found “large and persistent annual US goods trade deficits, constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and economy of the United States.”

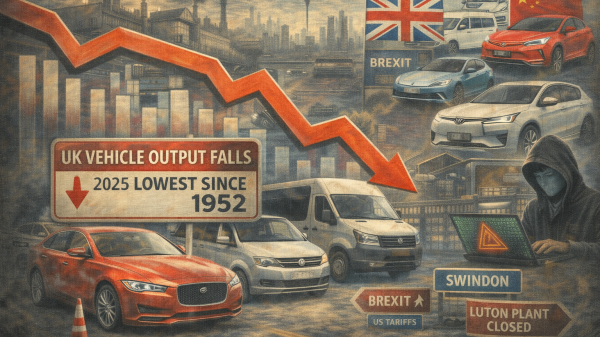

Based on this emergency, the President announced a package of tariffs on every country in the world, including those with whom the US has a trade surplus, like the UK and Brazil. These “Liberation Day” tariffs were explicitly aimed at addressing foreign countries’ tariff barriers, non-tariff barriers, and “cheating.” They used an objective formula – the values of the trade deficit divided by the countries’ exports to the US, then divided by two, with a minimum of ten percent to address this. As I mentioned earlier in these pages, among other things, this formula punished poor countries for the crime of being too poor to buy US goods. At least, however, these tariffs were tied to the ostensible emergency.

Since then, however, we have seen revisions to the tariffs in a variety of unpublished deals that do not explain the reasoning behind the revisions. In some cases, the President has seen fit to impose large tariffs for other reasons. In the case of Brazil, which, as mentioned, has a trade surplus with the US, it is because of the supposed persecution of former President Bolsonaro, a Trump ally, and Brazilian censorship of American social media platforms. Ongoing difficult negotiations with Canada have been further complicated by the President’s reaction to Canada’s possible recognition of Palestinian statehood. India has been threatened with very high tariff rates over its ongoing trade with Russia.

An additional demand also became apparent with the Japanese “deal” and some subsequent ones. The President has said that Japan will invest $550 billion in the US at his personal discretion. Other trade partners, like the EU and Korea, have supposedly agreed to invest similar sums on similar terms, although the EU is denying it. If true, it gives the President what is essentially a trillion-dollar-plus sovereign wealth fund for his personal use.

By this point, your constitutional hackles should have been raised. To begin with, the founders warned that emergencies provide dangerous pretexts for executive overreach. The Federalist warned in various places that, while powers to deal with crises were necessary, they must be subject to checks and balances like all other executive powers. So, Congress must control the purse and, alongside the judiciary, guard against executive abuse of emergency power.

Power of the purse is central to a second aspect the Founders warned about – the Executive must not have the power to tax. That is squarely a Congressional duty to reflect the consent of the governed to taxation (the President, though elected, is more remote from the people.) Nor did the Founders think a tariff was something different from a tax, as some of the President’s supporters maintain. In Federalist 35, for instance, Alexander Hamilton asks what if the power to tax was constrained to import duties (as some anti-federalists were demanding), plainly viewing tariffs as a subset of taxation powers.

The corollary of this is that the President can have no separate source of revenue from that directed by Congress. In Federalist 58, Madison states clearly, “The House of Representatives cannot only refuse, but they alone can propose the supplies requisite for the support of government.” The idea of a President directing a sovereign wealth fund with monies provided by foreign governments falls manifestly outside this constitutional design.

Indeed, the Founders were worried about Presidential patronage power in general. They constrained the President’s appointment power with the consent of the Senate and, as Madison said in Federalist 48, “The legislative department alone has access to the pockets of the people,” thereby dissuading “projects of usurpation” by the Executive in this way.

Congressional silence on the President gaining control over a foreign-funded trillion-dollar fund to dispense patronage would be exactly the sort of thing Madison warned about when he said “a mere demarcation on parchment of the constitutional limits of the several departments, is not a sufficient guard against those encroachments which lead to a tyrannical concentration of all the powers of government in the same hands.”

A President declaring a “national emergency” over a trade imbalance or overcapacity in foreign markets, leading to his imposing taxes on Americans without Congressional deliberation or scrutiny, and possibly gifting him a massive pool of funds he could use for patronage, is exactly the sort of thing the Constitution was designed to prevent. It violates the separation of powers, eludes democratic accountability, and fits the pattern of emergency overreach our Founders repeatedly warned against throughout the constitutional debates. Even the biggest fan of an energetic executive, Alexander Hamilton, wanted to make sure that most of these powers remained firmly under Congressional control.

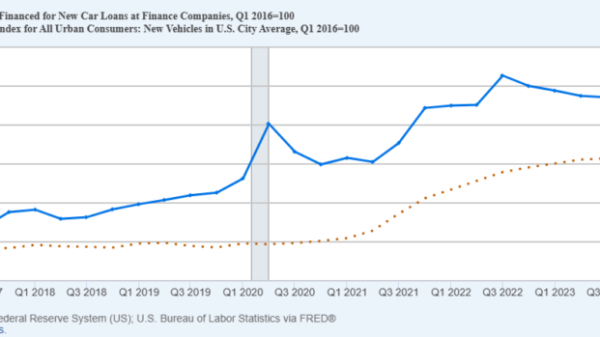

Indeed, Hamilton, supposedly the father figure of American protectionism, made many of the same arguments that free market economists make today about the abuse of tariffs as a revenue source. In the aforementioned Federalist 35, Hamilton says explicitly that “the consumer is the payer,” recognizing that the tax burden falls not on the foreign exporter, but on the American consumer. Indeed, this is why he recognizes that tariffs cannot be the only source of revenue for the federal government, as their burden would fall inequitably on the poor.

Hamilton recognized the problem of dispersed costs of tariffs — while they may initially seem painless because consumers don’t see the tax obviously, the total cost can become “oppressive.” In other words, tariffs are regressive. They are also therefore self-limiting, deterring imports, and thereby further revenue, when set too high. This provides another reason for the power to tariff to be confined to the legislature, which, as the people’s representative, can quickly respond to economic problems affecting specific sectors.

One final point is worth making about Hamilton. In the “Report on Manufactures,” the ur-text of American protectionism, the tariffs Hamilton proposed were modest by comparison with the President’s proposals, perhaps in consideration of the points he had made during the ratification debates. Indeed, the Report suggests that in many cases subsidies (or “bounties”) were preferable to tariffs as a means of encouraging industries, although Hamilton admits they may become the object of corruption, making it “necessary to guard, with extraordinary circumspection, the manner of dispensing them.” The President’s trade policy goes well beyond any of this. As Samuel Gregg has argued, the Founders wanted America to be a commercial republic. The President’s tariffs and the manner in which they have been used suggest not only a hostility to commercial trade, but to a republic with an executive constrained by co-equal powers. Congress, so far, has failed to guard its privileges. The Courts may not be so quiescent.