Substantive change has occurred in the subjects examined in my second book, Gold and Liberty (AIER, 1995), since it was published three decades ago. That change has been mostly negative, unfortunately, especially during the first quarter of this century. As economic liberty has decreased, gold has increased, a historical pattern which is by no means random.

The theme of Gold and Liberty is straightforward: the statuses of gold-based money and political-economic liberty are intimately related. When a government is sound, so also is money. One of the book’s premises is that sound money is gold money (or gold-based money) because it’s economically grounded, non-political, and exhibits a fairly steady purchasing power over long periods. A second premise is that while sound government makes sound money possible, sound money alone can’t ensure fiscal-monetary integrity in public affairs.

A sound government is, in this sense, one that respects private property and the sanctity of contract, a state that’s constitutionally limited in its legal, monetary, and fiscal powers. Sound money is a predictable and reliable medium of exchange, serving as a reliable yardstick due precisely to the relative stability of its real value (that is, “the golden constant”). Unrestrained states “redistribute” wealth rather than protect it, tending to spend, tax, borrow, and print money to excess. That erodes an economy’s financial infrastructure.

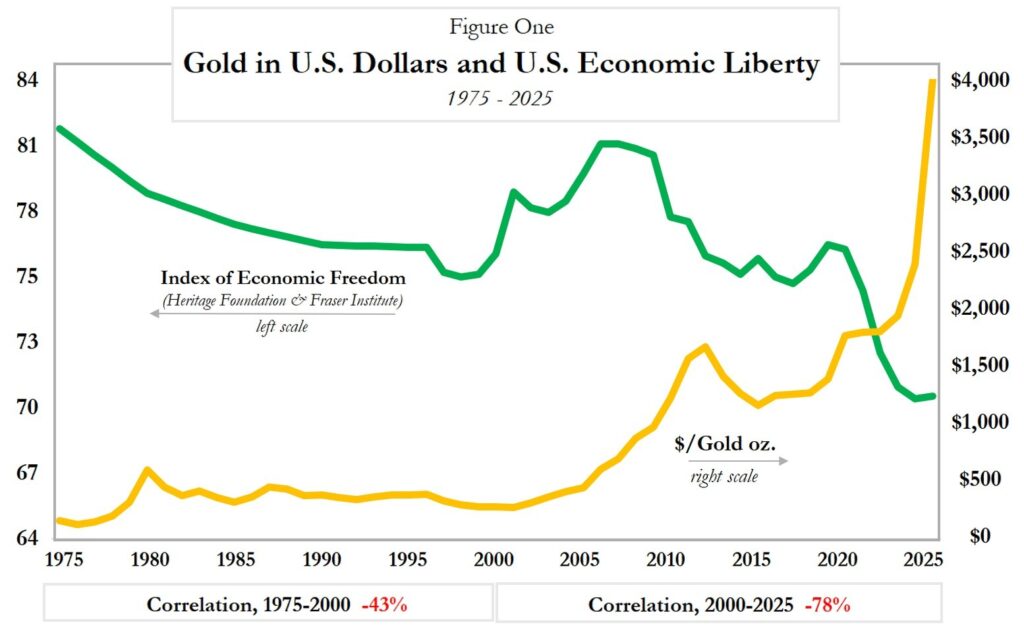

The dollar-gold price reached yet another all-time high milestone ($4,000/ounce) in October, having surpassed $3,000/ounce last March and $2,000/ounce only thirty months ago. So far this month, it has averaged $4400/ounce – triple its level in March 2020 (when COVID lockdowns and subsidies began). Gold breached $1,000/ounce sixteen years ago, amid the financial crisis and “Great Recession” of 2009. Only two decades ago, it was $500/ounce.

What Bretton Woods Got Right

Under the relative discipline of the Bretton-Woods gold-exchange standard (1948-1971), when the dollar-gold ratio was officially maintained at a steady level ($35/ounce), the Fed’s main job was to keep it there and issue neither too few nor too many dollars. Its job was not to manipulate the economy by gyrating interest rates. The dollar wasn’t a plaything in foreign exchange. Both US inflation and interest rates were relatively low and stable – not so since.

Gold and Liberty illustrates how the commonly cited dollar-price of gold is really the dollar’s value (purchasing power) in terms of real money, such that a rising “gold price” reflects the dollar’s debasement by profligate politicians. When this occurs – due largely to perpetual expansion of the fundamentally unnatural, unaffordable, and unsustainable welfare-warfare state – public finance (spending, taxing, borrowing, money creation) becomes both political and capricious. At the base there’s an erosion of real liberty. From that comes money debasement, the trend since the US left the gold-exchange standard in 1971.

The value of a monopoly-issued (fiat) currency reflects the competence and quality of public governance no less than a stock price reflects the competence and governing quality of a private-sector company. The empirical record makes clear that the US dollar held its real value (in gold ounces) for most of the period from 1790 to 1913, when government spending was minimal and there was no federal income tax or central (government) bank. In contrast, since the US established its money monopolist (the Federal Reserve) in 1913, the dollar, whether measured as a basket of commodities or consumer goods, has lost roughly 99 percent of its real purchasing power, most of that since the abandonment of the gold-linked dollar in 1971.

Debasement doesn’t get much worse than 99 percent – unless the loss occurs quickly and catastrophically, as in a hyperinflation. That’s not impossible in America’s future.

Having re-read Gold and Liberty recently, I feel both pride and chagrin. I’m proud that it refutes many monetary myths, gets the analysis basically right, and is prescient. It’s got solid data, history, economics, and investment advice. But its main, most helpful purpose is to make clear that money, banking, and the economic activity they support remain sound only in a capitalistic setting. That is, when government sticks to protecting rights to life, liberty, and property, by providing the three necessary functions of police, courts, and national defense.

Measures of Gold and Freedom

Why was this not the path taken this century? Why has government been expanded so much that it now routinely violates rights and spreads chronic fiscal-monetary uncertainty? Where’s the case, made so well in the second half of the twentieth century, for a more classically liberal political economy? In short, where have all the pro-capitalists gone? They were once dominant – and influential. Given the foundation laid by “Reaganomics” (1980s), the end of the USSR and the Cold War (1990s), plus US budget surpluses four years running (1998-2001), the first quarter of the twenty-first century could have entailed a still-purer capitalist renaissance. Instead, vacuous voters and pandering politicians from everywhere along the ideological spectrum have preferred more welfare, more warfare, and more lawfare. Many youths in recent decades tell pollsters they prefer socialism to capitalism (whether from ignorance or malevolence isn’t clear). New York City now has an overtly socialist mayor. Compared to 1995, America now has a larger, but still-burgeoning, welfare-warfare state that necessitates massive borrowing and money printing, as tax avoidance and evasion tend to cap the state’s direct “take” (see Hauser’s Law).

Unfortunately, the gains of the last quarter of the last century seem to have been squandered in the first quarter of this century. Monetary myths persist. Some have proliferated and worsened. Statists push a capricious “modern monetary theory” in hopes of more easily funding a burgeoning welfare-warfare state with minimal resort to taxation. Influential Keynesians and policymakers still insist that inflation is caused by “greed” or by an economy that “overheats” and thus warrants a periodic recession. Central banks this century seem more reckless and resistant to rules compared to the 1990s, as they unabashedly fund profligate states by chronic debt monetization, and their supposed “independence” dissipates.

One metric not available for the 1995 book was an index of economic freedom by nation, globally. This was still in the early stages of development. Two main measures have been constructed by the Heritage Foundation in Washington (since 1995) and the Fraser Institute in Canada (with indexes in five-year intervals extending back to 1955). An account of long-term trends in both gold and liberty would be interesting.

Figure One plots the dollar-gold price and the index of economic freedom (a splice of the Heritage-Fraser measures) since 1975. If the gold-liberty thesis is plausible, we should see an inverse relationship, or negative correlation, between the variables: liberty up, gold down or instead liberty down, gold up. That’s just what we observe. Indeed, it’s a more inverse relationship in the latter half of the period (2000-25) compared to the first half (1975-2000). Since 2008, the gold price has ascended while US economic freedom has descended.

Figure Two plots the dollar-gold price and US economic freedom for this century only. The inverse relation between gold and liberty is even more noticeable.

A few years ago, only three countries were economically freer than the US in 2007, but by 2015 11 nations were freer (I documented this as “The Multiyear Decline in US Economic Freedom”). Today, 24 are freer than the US. I wrote then:

most people, including many professional economists and data analysts (who should know better) seem to cling to the impression that US economic freedom is high and stable, while China has become less free economically. The facts say otherwise, and the facts should shape our perceptions and theories. Human liberty also should matter; much of our lives are spent engaged in market activity, pursuing our livelihoods, not in political activity. Finally, as a rule (which is empirically supported) less economic freedom results in less prosperity. Neither major US political party today seems much bothered by the loss of economic freedom. They don’t talk about it.” I added that “without a reversal in the trend of declining economic freedom in the US, we’ll likely be suffering more from less liberty, less supply growth, and less prosperity.

Recently, the relative holdings of foreign central banks are shifting away from large portfolios of US debt securities to gold. In dollar value, the world’s central banks now hold more gold than US securities. But this is due mostly to gold’s price boom relative to the prices of US Treasury notes and bonds, not to any material rise in the banks’ physical gold holdings. In short, the shift is an effect, not the cause, of gold’s price rise. The latter is due to the Fed’s excessive issuance of dollars, which is due to the US Treasury’s excessive issuance of debt to be monetized, which is due to the US Congress’s excessive spending, which in turn reflects a government no longer limited by a constitution or a gold standard.

Central banks could have sold some gold in recent years to rebalance the composition of their reserve holdings, but they haven’t. Why not? Are they now “gold bugs?” One might hope that their refusal to diversify would make it easier to return to the gold standard, but that seems unlikely given the fiscal-monetary prodigality we’ve witnessed so far this century. Here’s how I explained it in the book, when I was more optimistic about a return to monetary integrity.

If there is ever a return to a gold standard, it will not be accomplished by convening government commissions, which do no real scholarship and are purely bureaucratic undertakings, which perpetuate existing policy. Nor will a gold standard ever be properly managed by central banking, which is inimical to gold. The return to gold will require a sustained intellectual effort from academic economists and monetary reformers who uphold free markets, the gold standard, and free banking. It will require a major shift away from the welfare state that central banks are enlisted to support. Above all, it will require a return to classical liberalism based on a sound philosophic footing of respect for individuals and their right to be as free as possible from coercive government.

Meanwhile, it is encouraging that gold increasingly is in the hands of market participants instead of central banks. Since 1971, investors all over the world have been buying gold in the form of coins, bullion, and gold mining shares, primarily to protect their savings against the ravages of unstable government money. Meanwhile, although central banks and national treasuries continue to sit atop most of the gold they last held as reserves under the Bretton Woods system, they have somewhat reduced their gold holdings via sales and, more significantly, greatly increased their holdings of government debt. Gold now is a far smaller proportion of official reserves than it was in 1971. If these trends persist, the world’s central banks will be known solely as repositories of government debt, not of gold. In 1913, central banks and government agencies held about 30 percent of the world stock of gold. This proportion reached a peak of 62 percent in 1945 before falling back to 30 percent today. Where is this percentage headed? Central banks and governments as a group tend not to accumulate gold anymore and occasionally they sell it. Meanwhile, the world’s gold stock grows 2 percent every year. So the portion of gold held by governments should continue falling, absent a policy shift. With less and less of the total world stock of gold held by central banks and national treasuries, a greater portion is held privately. This was the situation before the rise of central banking. With the legalization of gold ownership and gold clauses, one might envision a return to gold de facto.

Why Gold Has Won

In 2020, recognizing that a return to a gold standard was less likely with every passing year (and crisis), I advised a gold-based price rule the Fed could follow (“Real and Pseudo Gold Price Rules,” Cato Journal). It’s a practicable, efficient system, but the Fed doesn’t consider it – and I can guess why. Central banks can’t afford to listen to reason, given their powerful and needy clients: deficit-spending treasuries and legislatures. As I wrote:

Most central banks in contemporary times attempt monetary central planning without a clear or coherent plan, consulting an eclectic array of measures without focus. In effect, they rule without rules. Economists by now are reluctant to recommend rules that central banks are neither motivated nor required to adopt and would drop in haste in the heat of the next crisis. Much monetary policymaking now embodies the subjective preferences of policymakers and their clients: overleveraged states.

It’s as clear now as it was in 1995 that gold is an ideal monetary standard, even though sovereign powers at times (and for the entirety of this century) have refused to recognize or use gold for that crucial purpose. But consider just one important implication, pertaining to investments. Precisely because (and to the extent) sovereigns refuse to recognize gold, to be fiscally free (profligate), the result is nonetheless bullish for gold. By not making their money “as good as gold” and precluding a return to a gold standard, sovereigns make possible returns on gold that are very good indeed – often superior to those on the most popular alternative: equities. Table One illustrates how fiscal profligacy and monetary excess have favored returns on gold relative to those on the S&P 500. Not shown is that gold has outperformed the S&P 500 in nearly two-thirds of the years this century, by an average of +17 percentage points per year; it underperformed only one-third of the time by an average of -14 percentage points. Oddly, most investment advisors eschew gold and routinely recommend large portfolio shares in equities.

Friends of liberty and prosperity may feel chagrin, as do I, about this century’s innumerable, unnecessary financial debacles. But they can also feel consoled, satisfied, and even gleeful if they’ve trusted gold more than central bank alchemists. They’ve likely been mocked – by fans of fiat currency or cryptocurrency alike – for clinging to their “mystical metal,” “shiny rock,” or “barbaric relic.” But name-calling isn’t a good argument – nor good investment strategy.