The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is expected to leave its interest rate target unchanged at 3.5 to 3.75 percent at this week’s January meeting. After a series of rate cuts in the second half of last year, and a continued push for further easing, a pause may feel anticlimactic. But the leading monetary policy rules suggest another cut would be a mistake.

The latest Monetary Rules Report from AIER’s Sound Money Project shows that the Fed’s current policy rate now sits below the range suggested by several well-known rules. Most of the rules point to an appropriate policy rate somewhere between 3.85 and 4.25 percent, depending on how one weighs inflation, employment, and overall spending in the economy. In that context, additional rate cuts would go beyond what current economic conditions justify.

Why Stop Here?

Chair Jerome Powell has described the Fed’s recent rate cuts as “risk-management” moves — steps taken to guard against the possibility that a cooling labor market could tip into something worse. That framing made sense last year, when unemployment was drifting upward and the outlook for growth was more uncertain.

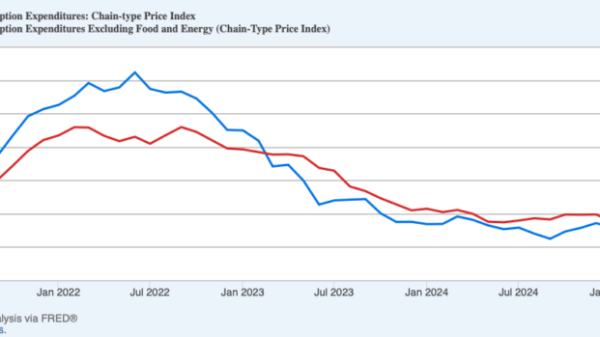

Since then, the economic picture has changed. Despite a continued slowdown in job creation, the unemployment rate in December was only slightly higher than in the first half of the year. More importantly, real GDP grew much faster than expected in the third quarter of 2025, as total spending in the economy rebounded sharply. At the same time, inflation remains above the Fed’s two-percent target, and progress toward that goal has been uneven.

The risks that motivated rate cuts last year have not disappeared, but they no longer justify continued risk-management through easier monetary policy.

What the Rules Say

Monetary policy rules provide a consistent way to translate economic conditions into interest-rate guidance, helping policymakers avoid overreacting to the latest headline or political mood.

Rules based on inflation and unemployment — often referred to as Taylor Rules — suggest that the policy rate should be closer to 4 percent. This prescription is based on a few key factors. First, inflation remains stuck persistently above the Fed’s two-percent target. When inflation is above target, the Taylor Rule calls for higher interest rates to slow demand and reduce upward pressure on prices. Second, the unemployment rate remains close to levels typically associated with maximum employment. When the labor market is near maximum employment, the Taylor Rule suggests there is little need for lower interest rates to boost economic activity. Third, strong growth and productivity have led to an increase in estimates of the “natural” rate of interest — the interest rate that is expected to prevail when the economy is at full strength and inflation is stable. When the natural rate rises, the Taylor rule calls for a similar increase in the prescribed policy rate.

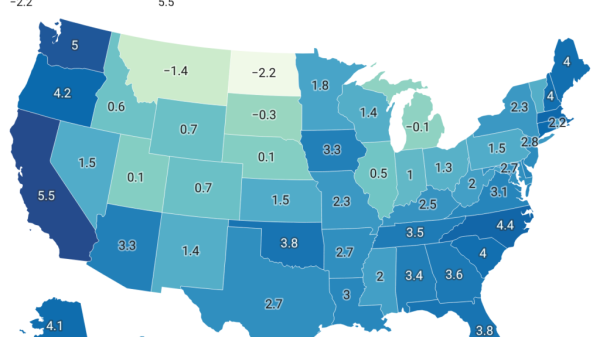

Rules that focus on overall spending in the economy — often described as nominal GDP (or NGDP) targeting rules — call for an even higher policy rate. Total spending by households, businesses, and governments grew briskly in the third quarter of last year — over 8 percent on an annualized basis — signaling that monetary conditions are not especially tight. When spending accelerates that quickly, cutting rates further risks adding fuel to demand at a time when inflation has not yet been fully contained.

What This Means for Monetary Policy

Coming out of the pandemic, monetary policy swung sharply — first, staying too loose as inflation surged, then tightening aggressively to regain control. Episodes like these highlight the danger of letting policy stray from the data. Rule-based benchmarks help guard against that risk by keeping policy anchored to observable economic conditions.

Right now, those benchmarks are sending a clear signal: there is no urgency to do more. If anything, they indicate that the next interest rate move — if there is one at all — should be up rather than down. While a reversal at this meeting is unlikely, the Fed’s internal debate should be about whether to regret the last 25-basis-point cut, not whether to cut even further.

That does not mean the Fed should ignore downside risks. Weak job growth, consumer spending increasingly driven by high-income households, and open questions about how long the AI investment boom will last are all legitimate concerns that should be monitored. At the same time, new jobless claims are near historical lows, growth forecasts are strongly positive, and the stock market is at record highs. Ultimately, monetary policy should not be driven by headlines in either direction. The Fed’s mandate is to promote maximum employment and stable prices. If unemployment rises, inflation falls convincingly toward target, or growth slows, the case for continued easing would strengthen. Absent those developments, further rate cuts are difficult to justify.

Looking Ahead

In the years immediately following the pandemic, monetary policy drifted away from the guidance offered by the leading monetary rules. Over the past year, the Federal Reserve has largely worked its way back toward those benchmarks, bringing the stance of policy closer to what prevailing economic conditions would suggest. That course correction has helped restore some measure of predictability and discipline to monetary policy.

The challenge at the start of 2026 is to maintain that discipline. Markets increasingly expect further rate cuts and there is political pressure to deliver on those expectations. But the greater risk now is repeating a familiar mistake: allowing policy to once again drift away from the signals embedded in the data. Absent clear signs of economic weakness, further easing risks undoing the discipline that has brought policy back on track.