The semiconductor industry is being rewritten by politics. What started as a response to COVID-era chip shortages and US–China tensions has turned into a structural shift: governments are pouring billions into domestic fabrication, tightening export controls and pushing for “technology sovereignty”. For IoT hardware makers, this is no longer an abstract macro trend—it directly affects where you source MCUs, connectivity chipsets and sensors, how you design boards, and how resilient your bill of materials really is.

Recent research highlighted by IoT Business News shows that, even as capacity improves, chipset lead times for IoT devices remain structurally higher than before the pandemic, and will likely stay constrained despite new fabs coming online. At the same time, policies such as the US CHIPS and Science Act and the EU Chips Act are explicitly framed around supply-chain resilience, not just advanced-node computing. The result is a progressive localization of semiconductor value chains that is now reshaping the economics and geography of IoT hardware.

From globalised chipmaking to policy-driven localization

For two decades, IoT and embedded designers benefited from a highly globalised semiconductor model. Design might happen in California or Europe, wafers would be fabricated in Taiwan or South Korea, packaging in Southeast Asia, and modules assembled in China or Eastern Europe. This density of specialized clusters drove scale and cost efficiencies that made it viable to put connectivity and compute into everything from smart meters to pet trackers.

The pandemic and subsequent supply crunch exposed how fragile that configuration was. A disruption in a single Asian foundry could stall entire automotive or industrial IoT programs worldwide. Government and industry responses since 2021 have followed a consistent pattern:

Subsidise local manufacturing to de-risk exposure to a single region.

Impose export controls on advanced nodes and certain categories of chips.

Tie industrial policy to strategic domains such as AI, automotive and critical infrastructure.

As IoT Business News covered in “State of IoT 2024: Number of connected IoT devices growing 13% to 18.8 billion globally”, policymakers now explicitly cite chipset supply and IoT deployment as justification for semiconductor interventions.

How policy-driven localization differs by region

Although the direction of travel is similar, regional implementations differ substantially—something IoT hardware strategists need to understand when planning mid-term roadmaps.

United States – CHIPS and Science Act

The CHIPS and Science Act (2022) allocates tens of billions of dollars in subsidies and tax incentives to encourage domestic fabs and packaging plants, with an explicit focus on reducing reliance on East Asian manufacturing for both advanced and mature nodes. While media attention gravitates to AI and data-center GPUs, a significant share of planned capacity targets 28–90 nm processes that are crucial for IoT-grade MCUs, connectivity SoCs and power management ICs.

At the same time, export controls restrict shipments of certain high-end chips and tools to China, which affects where and how US and allied suppliers can manufacture or assemble IoT modules.

European Union – EU Chips Act and “Chips Act 2.0”

The EU Chips Act aims to double Europe’s share of global semiconductor production to 20% by 2030 and strengthen “technological sovereignty”. The policy combines support for R&D with state aid for “first-of-a-kind” fabs and open foundries. Recent approvals for large projects in Germany, including a new Infineon plant in Dresden, illustrate how industrial and automotive IoT are key target sectors for this investment.

Importantly for IoT, European policymakers are now debating a “Chips Act 2.0”, with proposals that explicitly include supply-chain transparency and coordination in the mid-range and legacy nodes heavily used in industrial control, smart energy and telecoms.

China – self-reliance and “Xinchuang”

In response to export controls and geopolitical pressure, China has made semiconductor self-reliance a centrepiece of its five-year plans. Public funds such as the “Big Fund” back domestic champions across foundries, memory and equipment, with targets to dramatically increase self-sufficiency in semiconductor equipment and components. At the same time, the broader “Xinchuang” initiative pushes government and state-owned enterprises to prioritise domestic chips—including those used in industrial IoT, smart city infrastructure and telecoms.

For foreign IoT OEMs that rely heavily on Chinese modules or manufacturing partners, this creates a more complex environment: local players may gain preferential access to domestic capacity, while export and procurement rules limit what foreign chips can be used in certain public or critical projects.

Other regions – Japan, South Korea, India and beyond

Japan and South Korea are doubling down on advanced-node alliances and memory, but also using subsidies to retain or attract specialty processes relevant to automotive and industrial IoT. India has launched incentive schemes to attract fabs and OSAT (outsourced assembly and test) facilities, positioning itself as a complementary manufacturing hub for both domestic and export-oriented IoT devices.

The common denominator: everyone wants a larger slice of the value chain, and they want it physically closer to their own industrial base.

What this means for IoT hardware supply chains

A shift from “global” to “multi-regional” sourcing

For many IoT OEMs, the key practical change is that a single, globalised sourcing and manufacturing strategy is becoming harder to sustain. Policy incentives and export regimes are nudging the ecosystem toward multi-regional production footprints, where the same product family may be built with different silicon and module combinations depending on end-market geography.

Research highlighted in “6 IoT semiconductor predictions for 2026” underlines this regionalization trend, noting that increased localization of IoT chip production and tightening export controls are reshaping where IoT-grade MCUs, connectivity ICs and sensors are designed and manufactured.

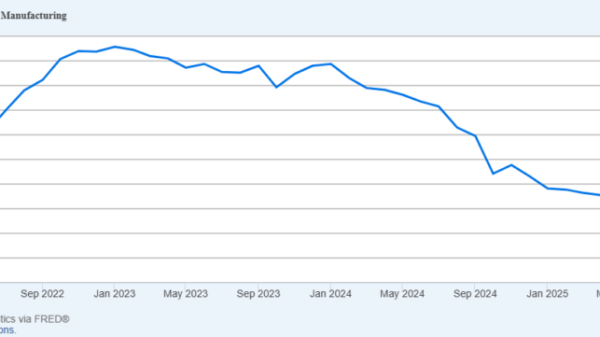

Persistent constraints at mature nodes

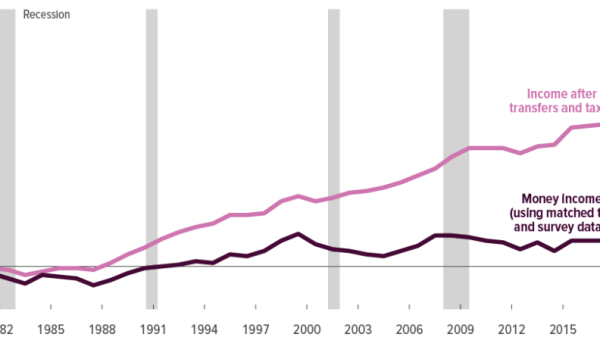

Even with new fabs announced, the picture is not one of sudden abundance. Much of the capacity under construction will come online toward the end of the decade, and a significant share is dedicated to leading-edge nodes that are less relevant for cost-sensitive IoT. IoT Analytics’ State of IoT research shows that chipset lead times have eased since the worst of the crisis but remain materially higher than pre-COVID baselines and are expected to stay constrained for years, especially once demand rebounds.

For IoT device makers, this means:

Planning for longer qualification and sourcing cycles.

Expecting price dispersion between regions, depending on local incentives and capacity.

Managing module and chipset variants more actively across SKUs.

New exposure at the second and third tiers

Semiconductor localization policies tend to be described in terms of headline fabs. But from an IoT perspective, risk is often concentrated in tier-2 and tier-3 suppliers: OSAT facilities, substrate providers, specialty analog and power component vendors. If these remain clustered in a small number of geographies, OEMs may still face bottlenecks even as wafer capacity relocates.

This is where supply-chain visibility—into where each critical component is designed, fabricated, packaged and assembled—becomes a strategic capability, not a procurement afterthought.

How IoT device makers are redesigning for localization

IoT manufacturers are already adapting their engineering and sourcing strategies to this new reality. Several patterns are emerging.

Designing for silicon flexibility

Building boards that support multiple pin-compatible MCUs or connectivity chipsets (e.g., different LTE Cat 1bis or NB-IoT modules) so that sourcing can pivot between suppliers or regions with minimal redesign.

Leveraging modular architectures—chiplets, RISC-V-based cores and configurable RF front-ends—to tailor silicon to regional regulatory and supply conditions while reusing as much design IP as possible.

Segmenting manufacturing footprints

Establishing dual or triple manufacturing paths (e.g., one in Asia, one in Europe, one in North America) and qualifying equivalent components across these.

Using regional EMS partners that can source from localised supply ecosystems while maintaining a harmonised global quality and test regime.

Integrating security and compliance into supply-chain design

Ensuring that device identity, firmware integrity and certificate management can be enforced consistently across regions and contract manufacturers—an issue explored in “Securing the Supply Chain: Protecting IP in IoT Manufacturing”, which links IP protection with EU cyber regulations.

Preparing for overlapping requirements such as the EU Cyber Resilience Act, data-localisation rules and sector-specific security mandates that increasingly influence where and how devices can be manufactured and provisioned.

Policy localization and the cybersecurity dimension

Semiconductor localization is also a cybersecurity and regulatory story. Governments that subsidise domestic chip production are simultaneously tightening rules around critical infrastructure, cloud–edge architectures and device security. For IoT OEMs, this creates both obligations and opportunities.

On the one hand, stricter certification regimes and region-specific crypto or identity requirements can force redesigns of secure elements, roots of trust or secure boot implementations. On the other, closer proximity between regulators, fabs and industry can make it easier to shape standards and co-design compliant, silicon-level security features.

The convergence of hardware security baselines, as highlighted in recent IoT semiconductor predictions, suggests that features such as hardware root of trust, secure key storage and lifecycle-aware identity will become non-negotiable for many segments. Designing these capabilities once and rolling them out across regionally tailored hardware variants is emerging as a key differentiator.

Key risks to monitor in a localized semiconductor world

As with any large industrial policy shift, there are significant risks and unintended consequences that IoT stakeholders should track closely.

Fragmentation and compliance complexity

Divergent regional requirements (from subsidy conditions to export controls and cybersecurity rules) risk fragmenting product portfolios. Maintaining separate hardware baselines for each major market can quickly erode economies of scale if not managed carefully.

Overcapacity in some nodes, shortages in others

A subsidy race that concentrates too much investment in high-profile advanced nodes could leave mature and specialty processes—those most critical for IoT and power electronics—under-served. Conversely, poorly coordinated incentives might trigger local overcapacity and pricing volatility in some process nodes or regions.

Uneven access to domestic capacity

In markets that favour domestic champions, foreign IoT OEMs may find themselves at the back of the queue for localized capacity, especially during demand spikes. This reinforces the need for multi-sourcing strategies and strong relationships with both global and regional suppliers.

Geopolitical miscalculation

Export controls and technology-sovereignty measures are inherently political tools. Escalation—whether through broader controls, sanctions or retaliatory measures—could rapidly disrupt established supply chains, especially for mixed-origin products that cross multiple jurisdictions.

Strategic takeaways for IoT leaders

For IoT OEMs, module vendors and enterprise adopters, semiconductor localization is not a temporary distortion but a new structural context. A few practical implications follow:

Treat silicon strategy as part of corporate risk management. Board-level discussions about geopolitical risk and critical infrastructure should now explicitly cover semiconductor sourcing and the specific nodes and components your products depend on.

Build “policy-aware” product roadmaps. When planning new device generations, factor in how CHIPS-like incentives, export controls and regional security rules are likely to evolve over the lifecycle of your hardware, not just at launch.

Invest in design flexibility and observability. Dual-sourcing, pin-compatible alternates, and clear mapping of each chip’s design–fab–OSAT chain are becoming as important as traditional cost and performance metrics.

Use localization proactively in your value proposition. In some markets, locally fabricated or regionally sourced silicon can be a selling point for public sector or critical-infrastructure projects, especially where digital sovereignty is a formal policy objective.

Semiconductor localization will not make IoT hardware simpler. But organisations that consciously integrate policy, engineering and supply-chain disciplines can turn this complexity into resilience—and, in many cases, into competitive advantage.

The post Semiconductor Localization: How Regional Policies Are Reshaping IoT Hardware Supply Chains appeared first on IoT Business News.