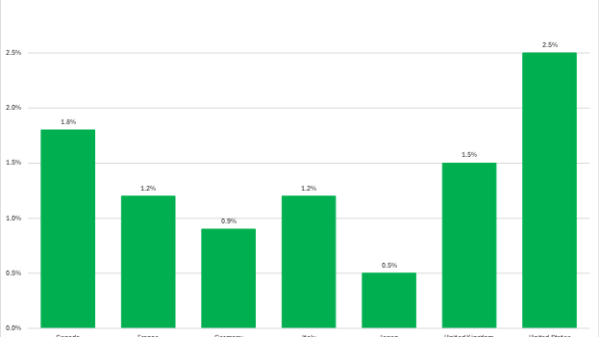

In a recent analysis gone viral, financial blogger Michael W. Green traced how modern American families can earn anywhere from $40,000 to $100,000 and still fall further behind. The argument is devastatingly simple: the mathematical parameters defining “poverty” are built upon a benchmark drawn in 1963, multiplied by three, and only lightly adjusted for inflation. Everything else — childcare, healthcare, housing, transportation, and the structural design of the welfare state — has transformed beyond recognition. The result is a system in which the official poverty line tells us less about deprivation than it does about starvation. And once you trace the math, the inescapable metaphor emerges: America’s working households require escape velocity to break free from the gravitational well of modern costs of living.

In physics, escape velocity is the minimum energy needed to break free from a body’s gravitational pull. Below that threshold, every burst of energy merely bends the trajectory and drops the object back into orbit. The same dynamic now governs mobility in the United States.

Using conservative assumptions, a bare-bones “participation budget,” the minimal cost necessary for a household to work, raise children, and avoid freefall, is roughly between $136,000 to $150,000. That figure doesn’t represent luxurious living; it’s the updated application of Mollie Orshansky’s original method, which assumed food was one-third of a household’s budget. Today, food is closer to 5 to 7 percent, and the real multipliers reside in the unavoidable costs of existing in a post-industrial service economy. The system still uses the original 1963 architecture, so the “poverty line” is measured as if housing, childcare, and healthcare still operated like they did during the Kennedy administration.

Below this new-era threshold, income gains are eaten by benefit cliffs: the loss of Medicaid, SNAP, childcare subsidies, and at that same point a sudden, full exposure to market prices in sectors that the United States has spent decades distorting through subsidies, mandates, and regulatory sclerosis. A family can leap from $45,000 to $65,000 and end up poorer, because the system confiscates more than 100 percent of that incremental income. From that perspective, it’s not irrational to stay put rather than aggressively seek higher earnings that will only bring more hardship and deprivation.

Using the 1963 poverty line today is like measuring the distance from Earth to the moon with a yardstick whose markings have been sandblasted away. It ensures two outcomes. First, because the benchmark is too low, benefits are means-tested too early. The ladder gets sawed off halfway up. The poor face marginal tax rates that would make a hedge fund blanch, and the working poor find that one extra dollar of income can trigger thousands of dollars in lost benefits. The mathematics are inherently punitive, punishing upward mobility and the productive instincts that animate it.

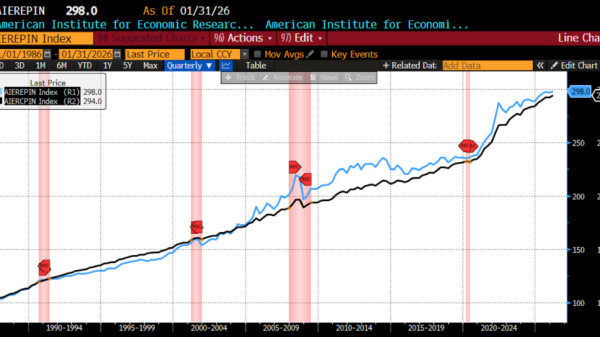

Second, persistent inflation, especially in non-discretionary categories, reshapes the spending basket faster than the poverty formula can adjust. This is not purely the result of supply-and-demand fundamentals. It is a direct consequence of decades of monetary expansion, financial repression, interest-rate suppression, and regulatory barriers that choke off the supply in housing, healthcare, education, and childcare. When the Federal Reserve aims to stabilize macroeconomic aggregates, it also inadvertently distorts the production of essential goods that determine whether a family can remain afloat. Price levels matter for survival even if economic science has come to prefer analyzing rates of change.

A similar mismatch between past prices and present reality — the real versus nominal divide — haunts the financial system. The $10,000 reporting requirement for bank transfers was created in the early 1970s, when $10,000 represented a down payment on a house. Today it represents two or three months’ rent in many cities — or a single dental emergency. Inflation has quietly turned an anti-money-laundering threshold into a mass-surveillance dragnet for normal people performing normal transactions. That same inflation, coupled with outdated benchmarks, now pushes American families into poverty by statistical invisibility and brutally repels attempts at upward mobility.

When escape velocity is $140–$150k, and the effective marginal tax rate is 80–120 percent, buying scratch-off tickets ceases to be obviously irrational. One needs a tremendous economic leap of roughly $100,000 a year to continue living without disruption. In a nonlinear system with cliffs and arbitrary phase changes, a low-probability high-payout gamble can be mathematically defensible. Tilting at heavy-tailed payoffs is not illogical; it is a response to a payoff structure policymakers engineered.

A likely response, politically, is to suggest simply lifting eligibility all the way up to the true cost-of-living threshold. But indexing benefits to the real cost of American life would balloon federal outlays by trillions. Extending Medicaid, SNAP, housing subsidies, and childcare credits to households making $140,000 would produce deficit dynamics that would make the 2020–2021 stimulus era look mild and restrained. The welfare state is already actuarially fragile; expanding it to cover half the US population would collapse it. On the other hand, three somewhat simple reforms could help restore a sane poverty escape velocity:

Use a modern participation-budget approach, not a 1963 grocery multiple. If there is to be a social safety net, it should be driven by means testing which phases out smoothly, not falls off cliffs.

Deregulate housing, healthcare, childcare, and education: the sectors where supply is most strangled by regulation. Deregulation — particularly zoning, certificate of need laws, licensing, and insurance mandates — would create downward price pressure far more powerful than subsidies.

The Federal Reserve’s century-long experiment with cheap money has inflated asset prices, destroyed purchasing power, raised the cost of entry into middle-class life, and widened the gap between wages and participation requirements. A quick fix could be rendered by shifting from discretion to a rules-based monetary regime (whether Taylor-style, commodity-linked, or another transparent, market-tested anchor) to stabilize prices and reduce the boom-bust cycles that erode household stability.

America’s primary poverty crisis is not moral failure, laziness, or poor financial literacy. It is math. A system built on 1963 assumptions cannot function in a 2025 reality. Until the parameters shift, which is to say until lawmakers acknowledge the true cost of participation, that escape velocity will remain impossibly out of reach for tens of millions. The tragedy is not that people are failing; it is that the system is calibrated for a world that has not existed in over three generations. There is no reform, no genuine improvement in the condition of the poor, no revival in the living standards of consumers — or of any American who works — without monetary reform beginning at the very top, with the Federal Reserve.