For all of living memory in the US, the decision of how to educate one’s children was easy.

It is largely taken for granted: when Johnny or Jenny turn five, they’re enrolled in kindergarten at the local public school. After five or six years at the assigned elementary, they’re bussed slightly farther to a regional middle and consolidated high school. If they do tolerably well in academics, they’ll be routed into SAT prep and meet with a guidance counselor about college.

There are choices involved, but they’re all peripheral ones. Should we buy a house in this district or that one? Should we enroll Emma in half-day or full-day kindergarten? Does Brett need an SAT tutor? How much summer reading should we insist on at home?

For 90 percent of American families, the biggest decision — how an individual child should be educated — is made by default. Most of us attended public school, and we all turned out fine.

But have we really? Public schools have been quietly failing well-meaning parents for generations.

Only 31 percent of American 4th graders read at or above grade level

Only 28 percent of American 8th graders can complete grade level math

54 percent of American adults read at or below a 6th-grade level – a trend that’s been stable for decades

The idea that Junior can go to public school and be “just fine” may not be as surefire as we thought.

The default consensus is at last unraveling, and the conscientious parent has begun to ask: Should I send my kids to public school at all?

The Quiet Failure of the Public School System

Public school wasn’t widely adopted across America until the 1920s, but within a generation, it was a core part of the American dream. Think of the 1950s cultural milieu – World War II veteran father driving off to work in his Chevrolet Bel Air, supporting his family on a single income while his wife kept house in her apron and bouffant while Dick and Jane walked themselves back and forth to school each day, books in hand.

In those short decades, the government-run school became a staple of American identity. In only the most remote corners of the country did the one-room schoolhouse still exist; bells and textbooks, homeroom and homecoming, school band and dances and plays had become as American as the moon landing and apple pie.

Older generations, many of whom had grown up without the advantages of a youth set aside for learning, extolled the importance of formal schooling, in both the preparation for life and the development of the self: I didn’t get to go past eighth grade, but my Bobby’s going all the way to college.

It was a utopian dream. Education for everyone, provided equally and fairly by the state, with recess and lunch programs to fuel the body while stern-but-fair teachers molded the mind.

But even from the very early days, there were cracks in the veneer.

In the 1950s, Rudolph Fleisch wrote a scathing critique of the American education system in his book Why Johnny Can’t Read, exposing the American literacy crisis that was already plaguing our society and undermining our future.

In the 1980s, the Reagan administration published A Nation At Risk, a landmark paper exposing America’s poor academic outcomes as a national security crisis. Its message was ominous: if we don’t fix American educational outcomes, they’ll become a threat to our future. The paper caused waves, but nothing in the system actually changed.

In the 1990s, John Taylor Gatto wrote his startling resignation letter from New York City Public Schools in the pages of the Wall Street Journal after being awarded Teacher of the Year – twice. In “I Quit, I Think,” and later in The Seven Lesson Schoolteacher, he confessed that he felt he was harming children by subjecting them to the public school curriculum. His books developed a passionate following, but the system carried on.

In the early 2000s, No Child Left Behind legislation was conceived to address what we’d by then been talking about for decades: public schools were deeply and fundamentally failing our children, and Americans faced a crisis of academic performance. The program’s enormous funding and resources didn’t change much, as measured by test scores, and its biggest lesson was that throwing money at our education problems doesn’t seem to make much difference.

And so, generation after generation, public schools failed to effectively deliver on their directive to educate the youth of one of the wealthiest and most powerful nations on the globe.

But no one particularly seemed to care – at least, not enough to create real change.

The Rise of Public School Alternatives

Finally, in the era of the internet, the momentum started to shift. Until the 1970s, homeschooling was largely unheard of (and in many states, illegal) but by the 2010s, it had become a part of the national lexicon. In 2015, there were well over 1.5 million homeschoolers in America, and slowly rising — enough to make a noticeable shift (~5 percent) in the ratio of American students enrolled in public K-12 programs.

Education entrepreneurship — for many years relegated to small mom-and-pop-style alternative schools, where it existed at all — began expanding. The momentum gathered slowly: Montessori schools in America doubled between 1990 and 2000 to over 3000, with hundreds of Waldorf schools right behind. Student-led programs like Acton Academy began to emerge in the 2000s; privately managed charter schools gained traction; online schools rode the wave of home internet access. As public schools became increasingly mired in standardized testing and national curricular standards, parents began searching for the exits.

Investors, seeing this widespread market for alternatives, backed innovative projects, and a generation of VC-backed education programs was born: Prenda, Primer, Synthesis, Guidepost Montessori, Alpha School. They focused on supporting new founders in making franchise-like programs available nationwide.

Alongside these broad-scope strategies, the microschool movement emerged. Fueled by frustrated teachers and disillusioned parents, hundreds of tiny, independent learning centers flickered to life and began to expand.

Outcomes for these schools and students are promising, but schools still struggle against the Goliath of public school as a cultural norm. The familiarity bias is hard to sway – public school was just fine for me; of course it’s good enough for my kids.

The End of School is Just the Beginning

The response to COVID-19 and the school shutdowns that followed accelerated the search for alternatives to “default” government schools. The pandemic was the breaking point for many parents, where they finally saw what was happening up close – not the statistics, not the reports, but the actual instruction occurring inside their kids’ classrooms when school came home via Zoom during the lockdowns.

This was perhaps one of the silver linings of the pandemic: when parents saw what school had really become (not at all what they remember) they wanted out.

Public school enrollment numbers dropped sharply and observers expect the decline will continue, with millions more children freed in coming years. Meanwhile, the ranks of homeschoolers swelled, as did the enrollments of alternative programs; everything from Montessori schools to innovative programs like Prenda and Synthesis saw a spike. At the height of 2020 closures, as many as six million kids were being homeschooled — not just doing public school at home, but intentionally going through a curriculum sourced or designed by their parents.

In the five years since, things have slowly stabilized, but the surge in school alternatives can’t be stopped. The balance has shifted. As of the 2024-2025 school year, only 49.4 million students are enrolled in public school, while estimates of the number of homeschoolers in America range anywhere from 3-5 million – which, on the high end, is one in nine American kids.

Fully 60 percent of families looked for schooling alternatives last year. One in eight parents now say they expect to homeschool their kids. The tide is turning.

The New Fight for School Choice

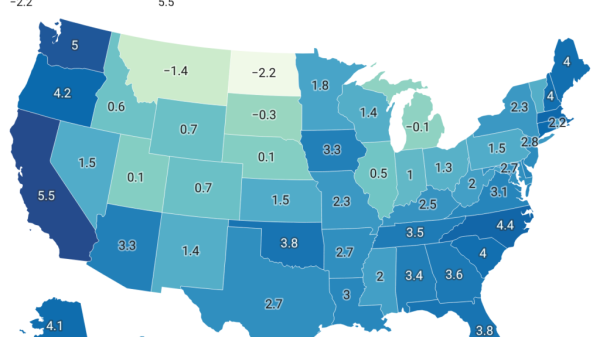

Funding is starting to catch up to the student exodus. Seventeen states now have universal school choice programs, and sixteen more help at least some families afford alternatives. These vouchers empower parents to choose for private school (ranging from $6,000 to $10,000 depending on the state), lessening the financial barrier to an alternative education.

Parents know that default schools have delivered decades of disappointment. Government-run schools were like the post office or the DMV… We went, we sent our kids, we trudged on, because what choice was there?

But now education has become a marketplace. The drab monopoly on teaching children has been challenged, and parents see an increasing variety of exciting answers popping up. Finally, parents can treat school not as an eventuality, but as a thoughtful consumer: “Is public school actually the best fit for my child?” And if not, even more enticingly, “what kind of education would serve him better?”